A short overview of the three phases of hot composting

/Just like us - microbes need food, water, and air to thrive. When you’ve created the right conditions (proper C:N ratio, moisture and aeration), you can expect three phases of the composting process to occur.

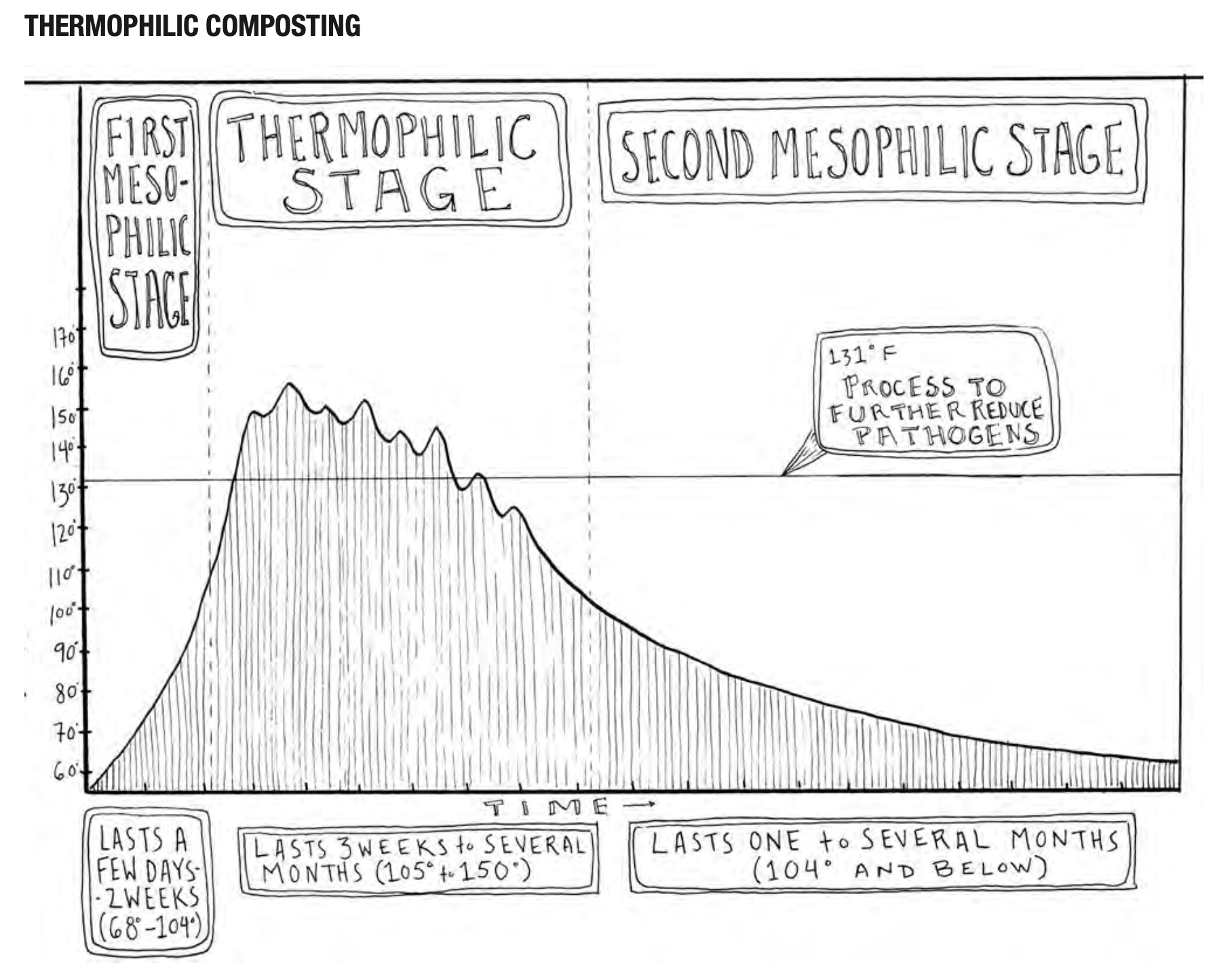

Phase 1: Mesophilic microorganisms, that thrive in temperatures around 68 to 113 degrees F, begin physically breaking down the material in the compost system. The process creates heat, and temperatures can quickly reach 100 degrees F and higher within a few days.

Phase 2: As the temperature rises, thermophilic microorganisms – which thrive in these higher temperatures – start to replace the ones that like those cooler temperatures. This group of microbes work to break down the organics into finer particles, and the higher temperatures are more conducive to breaking down complex carbohydrates, proteins and fats. This stage typically lasts from a few weeks to a few months.

Phase 3: This last phase begins when the available supply of these organic compounds within the compost system are used up. In this phase, the temperature starts to drop, and the population of mesophilic microorganisms rises again. This stage can last for several months, as this group of microbes finishes breaking down the remaining organic matter into stable humus. This is the curing process. It’s not uncommon to get a short spike in temperatures if you’re turning or aerating your compost during this phase, but it’s typically shorter-lived that the more active decomposition that happened in Phase 2.

Image from the NYC Compost project Master Composter Course Manual. Chapter 2: Composting. Page 2-21.

There are a few ways to tell if your compost is ready to use:

It has a pleasant, earthy odor

It’s dark and crumbly

The volume of the pile should have shrunk by about 50%

The temperature of the pile should be around air temperature

The original organic materials should no longer be recognizable, with a few exceptions (think avocado or mango pits, larger wood chips, etc.). These pieces can be screened or pulled out and tossed back in an active pile for another round.